الثلاثاء، مايو 24 مايو 2022

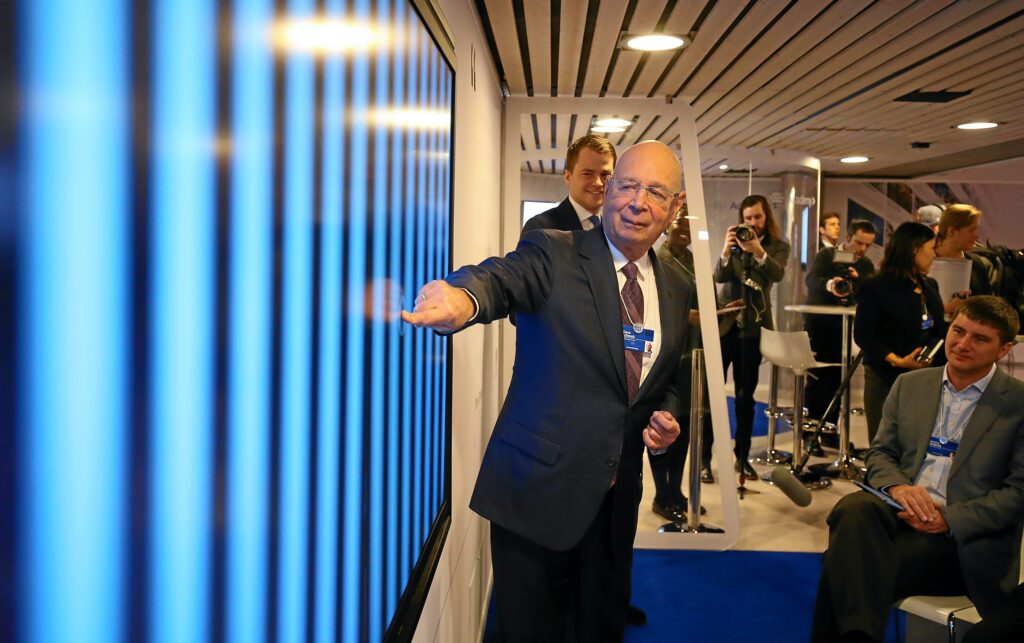

Conservative American journalist Jack Posobiec posted videos to Twitter this week recounting how he was detained by police at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos while attempting to report on WEF founder Klaus Schwab. The detainment brings up old questions surrounding Switzerland’s freedom of the press and how much power Swiss police have in curtailing it.

A video still of journalist Posobiec being detained in Davos.

More on Davos 2022

WEF has been hosting the annual five-day event in the Swiss resort town of Davos since the 1970s. It is an invitation-only event which brings together about 2,500 people: CEOs from 1,000 member corporations, as well as certain politicians, academics, religious leaders, members of the media and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

The meeting is historically held in January but was moved to May this year amid Covid-19 concerns. It is the first in-person meeting since January 2020. This year’s meeting will focus on the war in Ukraine, the global pandemic, environmental and economic crises under the theme “History at a Turning Point: Government Policies and Business Strategies.”

Journalist Jack Posobiec said he was investigating WEF founder Klaus Schwab (pictured above) “and his cronies” before being detained by Swiss police.

As many as 500 journalists from print, online, television and radio are in attendance, but not all invitees have access to all events. Clearance is given on a “badge” basis, with white badge holders having the most clearance.

“Davos runs an almost caste-like system of badges,” according to BBC reporter Anthony Reuben. “A white badge means you’re one of the delegates – you might be the chief executive of a company or the leader of a country or a senior journalist. An orange badge means you’re just a run-of-the-mill working journalist,” Reuben explained.

Journalist detained

In the videos that were posted online Monday, Posobiec is standing on a sidewalk in Davos when four uniformed and two plain clothes police officers approach him. The uniformed officers, presumably local Swiss police members, were wearing patches which identified them as “WEF Police.” They were carrying MP5s, a style of submachine gun used by SWAT teams.

“One of the guys is flagging me with his MP5,” Posobiec recounts in another video. “Each of us was taken, myself and the entire crew, one by one … behind the building and behind this stack of tables. And we were made to empty our pockets, and we were frisked,” he said.

Once a tiny mountain village, the World Economic Forum has made the town famous.

One of Posobiec’s film crew begins asking a policewoman in plain clothes questions.

“Is there a reason he specifically was targeted?” the crewmember asks.

“There is a reason, because we have to have a reason to control a person,” the policewoman says.

When asked what the reason was, the policewoman replies “I don’t have to tell you.”

The police then ask the crew to delete their footage and the video cuts off.

Filming Swiss police officers is protected under law, unless it interferes with their work or is done with the intent to disseminate the footage, according to Swiss police researcher and consultant Frédéric Maillard who spoke to SwissInfo about police reform.

“In general, citizens have the right to film the police and show the footage to a judge, for example,” Maillard said. “Police officers can ask people to stop filming using the argument that it’s impeding their work, and this, of course, can be abused or controversial. It all comes down to technique, and that’s also why I feel that two years of police training are not enough.”

Maillard is advocating that Swiss police training be increased from two to four years, as the “extra education would introduce more self-reflection, social and behavioral training as well as knowledge of our political and judicial systems into the curriculum.”

Were other journalists at Davos detained? No others have come forward.

Freedom of the press?

Switzerland this year dropped four places – from 10ال to 14ال – on the Press Freedom Index, according to the Reporters Without Borders. The United Kingdom ranks 24ال and the United States ranks 42nd.

وفقاً ل the report, the drop is due to “gaps in the legislative framework” and the “increasing number of provisional measures sought – and often obtained – against the media shows that Switzerland is not safe from so-called ‘muzzle’ procedures.”

For example, Switzerland’s famously secret Swiss banks are protected under law more so than the freedom of press.

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project keeps an updated page on all the latest news reported to the Suisse Secrets (graphic via OCCRP).

Suisse Secrets

In February 2015, reporters revealed that clients of the Geneva branch of HSBC included arms traffickers and blood diamond dealers. By July of that year, Article 47 of the country’s 1934 Banking Act went into effect which holds that anyone, including journalists, who “discloses information about bank customers to other people” can be punished by up to three years in prison, even if it is done to expose criminal behavior.

The punishment was increased to five years in prison amid a similar investigation which uncovered dozens of Credit Suisse accounts were held by dictators, criminals and human rights abusers.

These banking cases, which have come to be known as the Suisse Secrets, have been reported by more than 164 foreign news outlets, but not by any Swiss ones. When a Credit Suisse whistleblower approached Swiss newspaper تاغس أنزيغر with the information, the newspaper declined fearing prison sentences for their journalists.

“The fact that bank data is being leaked in foreign media today, while there is a ban on research in Switzerland, is an absurdity that must be abolished,” Arthur Rutishauser, editor-in-chief of Switzerland’s largest media group Tamedia, wrote in an op-ed.

If Swiss journalists are censoring their work over fears of being imprisoned, does freedom of the press exist in the Alpine nation?

‘The criminalization of journalism’

Earlier this month UN Rapporteur for the protection of freedom of expression Irene Khan announced that she sent a six-page letter to President Ignazio Cassis with her concerns that the law has resulted in censorship.

“On the one hand, there is a right to privacy. On the other hand, there is also a public interest in being informed about illegal financial transactions,” said Khan. She spoke with تاغس أنزيغر.

“The law must allow journalists to balance these two things. But this Swiss law criminalizes any publication from the outset, without exception. This goes too far,” Khan added. She says the Swiss government responded to the letter, saying that the law is being reviewed and that no journalists have been prosecuted, yet.

“The Swiss banking law is an example of the criminalization of journalism,” said Khan. “This could complicate investigative journalism on corruption in other countries.”

Khan added that on June 24 she will report to the U.N. Human Rights Council on press freedom in Switzerland.

يمكن مشاركة هذه المقالة وإعادة طباعتها مجاناً، شريطة أن تكون مرتبطة بشكل بارز بالمقالة الأصلية.