Di., Nov. 2nd 2021

Switzerland consistently ranks as one of the happiest countries in the world. UltraSwiss explores how the tiny Alpine nation earned and maintained its title.

Switzerland’s most famous peak — the Matterhorn — can be seen from a hiking trail in Zermatt.

If there is anything we can glean from the pandemic — a period in which we have been asked to live without offices, schools, shops and even each other — it is that our happiness is not irrevocably tied to our conditions. And while many of us are just now arriving at this conclusion, well-being experts say that Switzerland and a handful of other countries already had happiness figured out long before Covid-19 arrived on the scene.

The United Nations’ World Happiness Report, launched in 2012, ranks countries from happiest to unhappiest using metrics such as well-being and joy instead of economic success. Of the 149 countries the UN has studied over the last decade, rankings have shifted dramatically based on many factors such as natural disasters, changes in leadership and more recently, how countries handled the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite the worldwide shift in how we now live, the countries taking the top spots on the report have remained unchanged since the first report: Finland, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, the Netherlands and the place I’ve lived for the past seven years, Switzerland.

Like many expats living in Switzerland (and there are many — about 25% of the population), I believed that there was not much more to this country than cheese, chocolate and watches. But I found that the Swiss are much more than their movie stereotypes. Their brand of happiness is not something saved for their next vacation nor something to be acquired at a luxury store. The Swiss have come to expect happiness as a human right. It is in the Alpine air they breathe and the clean, glacial water they drink. It is in their world-class health care and robust economy. It is in their tight sense of community and attachment to traditions. Switzerland’s bar for happiness is both accessible and difficult to match among other first-world countries.

Virtually no tourists were traveling to Switzerland outside of affluent mountaineers until German physician Alexander Spengler lured them here in the 1860s, touting what he believed was the country’s ability to cure tuberculosis. Dr. Spengler arrived in the impoverished mountain village of Davos in the 1850s as a political refugee looking for work. He quickly observed that the residents were able to climb steep mountains “without perspiring or becoming breathless,” according to his letters to friends. The locals possessed “a beautiful, symmetrical body, a bulging chest and a strong heart muscle.” Most shocking to Spengler, there were no cases of tuberculosis in Davos at a time when one-quarter of the adult population of Europe was dying from the then-incurable disease.

While most well-off TB patients were traveling to Italy and the south of France in hopes that the warm air would cure them, Spengler believed something extraordinary was going on in the icy, high-altitude city. He began a letter-writing campaign to attract patients to Davos and in 1865 he began regularly treating them with a regimen he modeled after the locals’ daily routine.

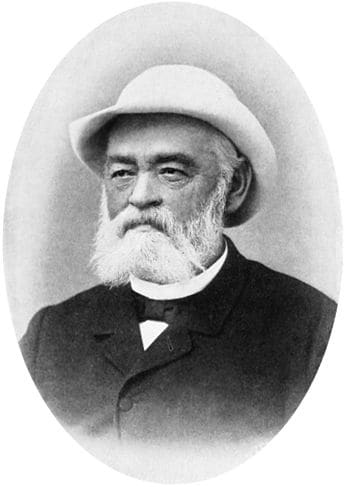

Physician Alexander Spengler, 1860.

In what is now believed to be the first spa in Switzerland, patients were prescribed to take long walks, ice-cold showers, massage their chests with marmot fat and lounge in the winter air. Spengler’s patients were also encouraged to eat light meals, drink three liters of milk a day and spend hours in cowsheds where their lungs would be filled with the ammonia-rich air. Spengler wrote that the treatment was a success and that his patients were able to “breathe more easily and deeply.”

By 1875, tourists from all over Europe were arriving in droves to the once-overlooked Swiss Alps. A railway line stretching from Zurich had to be built to accommodate them and foreign investors took note. Dutchman Willem Jan Holsboer built Switzerland’s first spa hotel with Spengler, the Holsboer-Spengler Hotel, which is still running today.

Dr. Spengler’s patients enjoyed being attended to by the staff of the Holsboer-Spengler Hotel, while recovering in the crisp Alpine air of Davos.

By the 20th century, Davos was regarded as a world-renowned health respite bringing in tourists for the entire country. In 1971 the first World Economic Forum invited leaders from around the world to Davos for a week of economic discussions; nearly everyone RSVP’d yes.

“[A]ny economic system that gives you a tax-deductible week in Davos at the height of the ski season must have something to recommend it, mustn’t it?,” a reporter for The Economist wrote. More than 100 hundred years after Dr. Spengler first began his letter writing campaign, Switzerland had become synonymous with spas, sports and health.

“Switzerland is one of the top international destinations for health tourism and wellness,” Thomas Goval said, the manager of the famed Bürgenstock Resort overlooking Lake Lucerne in central Switzerland. The hotel, which opened in 1873, has counted Charlie Chaplin, Audrey Hepburn and Sofia Loren among its guests.

The modern-day Bürgenstock Resort, located on the Bürgenstock mountain near Luzern. Crazy wonderful view, healthy Swiss food and service.

“The medical expertise and the high quality of the infrastructure in combination with the unspoilt nature and relaxing environment make our country a first-class year-round travel hotspot,” Goval said, adding that natural resources such as local herbs, Alpine air and glacial water have been used “for generations” for their “medicinal benefits.”

But, how does one put a price tag on clean air and water? Tourism statisticians estimate that about 36,000 tourists, on average, travel to Switzerland each year to be treated in its health clinics and medical spas. That tourism generates about $211 million dollars for a country that is just the size of Vermont and New Hampshire combined. Most of the country’s spa revenue actually comes from local Swiss citizens who frequent spas as part of their regular health routines. In fact, spa services and holistic health clinics are so important to Swiss citizens that in 2020 two-thirds of the country voted that they be covered by health insurance.

Davos, a once poor backwater village, has grown tremendously over the past century on the back of Dr Spengler’s efforts. Now, this thriving spa town attracts conferences and the wealthy from around the world, some of considerably controversy.

This sustained focus on health and relaxation contributes to a more long-lasting variety of happiness, according to Drs. Sonja Lyubomirsky and Kennon Sheldon.

“[T]he effects of positive circumstantial changes such as securing a raise, buying a new car, or moving to a sunnier part of the country tend to decay more quickly than the effects of positive activity changes such as starting to exercise, changing one’s perspective, or initiating a new goal or project,”Lyubomirsky and Sheldon write in a report titled Achieving Sustainable Gains in Happiness: Change Your Actions, Not Your Circumstances.

“The societal appreciation for health paired with a body and mind alignment helps people live longer,” Goval added. Swiss citizens rank second only to the Japanese when it comes to life expectancy.