Fr., März 10th 2023

Cultural objects encapsulate heritage and help to tell stories about our past, whereas the museums that collect them act as repositories, ensuring their longevity. Objects have such cultural importance that they come to embody national heritage. The paintings and sculptures by Swiss artists Ferdinand Hodler or Alberto Giacometti are, for example, symbolic of Swiss art history.

In some cases, however, it is not only the objects that tell stories but also their provenance. And there is no better example than the debate around the famous Benin Bronzes, a group of several thousand sculptures from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, providing a unique insight into the society, rituals and royal history of today’s Nigeria.

Yet rather than being displayed in Nigerian museums, these objects are spread across European collections, with a large number kept in the British Museum in London and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. At least 21 Benin pieces sitting in eight Swiss museums were recently proven to be stolen, with another 32 suspected to have been looted, as well.

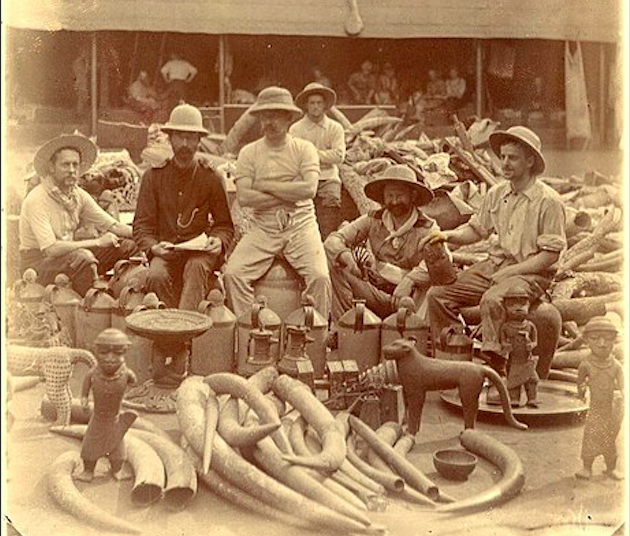

The British troops invaded the Benin Kingdom in 1897. During the attack, referred to as the Benin Expedition, over 10,000 cultural objects were looted, many of which were resold on the secondary art market.

While Switzerland was not directly involved in the looting, the recently completed Swiss Benin Initiative Bericht, published with the support of the Federal Office of Culture (FOC), demonstrated that 97 Benin Bronzes are currently held in Swiss public collections. A number of these objects were acquired in 1899, just two years after the attack.

However, others have entered museum collections as recently as 2022.

The report emphasizes the ethical relationship with the communities from which these objects were stolen and the need to build shared futures with colleagues from Nigeria. The joint declaration made by the participating museums, the representatives of His Royal Majesty the Oba of Benin and the Director General of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments of Nigeria states that objects likely to have been looted will be returned to the original owners, setting an example for approaches to colonial heritage.

This represents 54 objects from several collections; however, at the time of the publication, an official restitution request is yet to be submitted.

While Swiss authorities regularly return illegally traded cultural objects following the 1970 UNESCO convention, restitution is still a new process for public collections, with little precedent and much controversy.

In 1992, the Museum of Ethnography in Geneva voluntarily returned a Māori object to New Zealand, first as a loan and then as a permanent restitution. In February 2023, the city of Geneva returned a medicine mask and a rattle to the Haudenosaunee Nation in current-day Canada.

These new practices align with the global discourse on collaborative research and restitution, even though actual returns of objects have only recently taken place.

France led the way for Benin pieces with a restitution effort in 2021, after a report published by Bénédicte Savoy et Felwine Sarr in 2018 cited the nation’s large collection of Nigerian art. However to this date, only a handful of objects have been actually returned as the country is waiting for the Edo Museum of West African Art to be built in Nigeria.

In addition, Germany returned the ownership of more than 1000 Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in 2022, with 20 of these delivered in December. The London Museum gave back six Benin pieces in November 2022, but that appears to be the only pieces to return from the U.K. A Nigerian cultural minister has called on the British Museum to release the more than 900 Benin Bronzes, but no apparent answer has been made yet.

“We want to give Swiss museums the opportunity to return these works of art to their rightful owners and display them legally – to do the right thing,” Abba Tijani, director general of the National Museums and Monuments Authority of Nigeria, told SWI swissinfo.ch.

The Benin Bronzes are not a unique case. Some reports state that over 90% percent of Africa’s heritage is located outside the continent and, as ethnographic museums hold objects from all around the world, further research may result in new restitutions.

However, restitutions are only part of a global effort to rethink ethnographic collections. The Geneva Museum of Ethnography is taking a leading role in Switzerland as it plans to ‘decolonize’ its collection through an attempt to share the authority over the interpretation, documentation, and exhibition of the objects with the cultures they originate from. In its plan for 2022-2024, the museum warns that this is not a straightforward approach, but rather a process, which would be unique for each individual circumstance.

Academics often describe museums as places of soft diplomatic power, and rethinking the history and display of museum objects can be seen as the start of a conversation over the inequalities created by the European colonial past.

Dieser Artikel darf frei weitergegeben und nachgedruckt werden, vorausgesetzt, es wird auf den Originalartikel verwiesen.