mer, Juin 1st 2022

More than 40,000 Ukrainian refugees have been welcomed with open arms by Switzerland, which historians say breaks with Switzerland’s tradition of being closed to those fleeing repression and war. David Eugster of SWI swissinfo.ch takes a look back at how Switzerland has welcomed refugees over the years.

Switzerland has accepted more than 40,000 Ukrainian refugees; as well as, expediting the ratification of a special “S” permit which such refugees can apply for once they arrive.

The current warm welcome to Ukrainian refugees reminds many in Switzerland of the year 1956, when Soviet tanks rolled into Hungary. A wave of solidarity ran through Switzerland: church bells rang and people stood for a minute’s silence in tribute to what was then called the “unprecedented fight for freedom of the heroic Hungarian people.” Refugees from Hungary were given asylum unconditionally.

All that was required was “a wish on their part to come to Switzerland,” declared the federal government at the time. Hungarians were considered worthy of asylum in the country since they were freedom fighters in the great struggle against Communism. They were allowed to work and settle if they chose.

La Suisse traite-t-elle équitablement les réfugiés ukrainiens ?

From open arms to fear of the foreigner

This openness did not extend to everybody though. If someone did not fit the profile of an anti-Communist, they were less likely to be accepted. Refugees from Algeria in the 1950s were a good example of this selective policy. They too were fleeing from an anti-colonial war of independence. Yet they were classified as “persons in need” by the Swiss government as opposed to refugees.

In fact, the Swiss authorities routinely suspected them of being “extremists.” Even Egyptian Jews who decided in late 1956 to flee to Switzerland didn’t experience much of a welcome. In November 1956, Israel, France and Britain had occupied the Sinai Peninsula. Egypt branded Egyptian Jews as “Zionist” enemies of the state. Jews in Egypt experienced abuse and violence, their businesses were seized – a context reminiscent of previous pogroms. In Switzerland they were asked to move on after their arrival; their stay and their onward journey had to be arranged by Jewish organizations – a practice, which the Jewish community in Switzerland mastered from the Second World War.

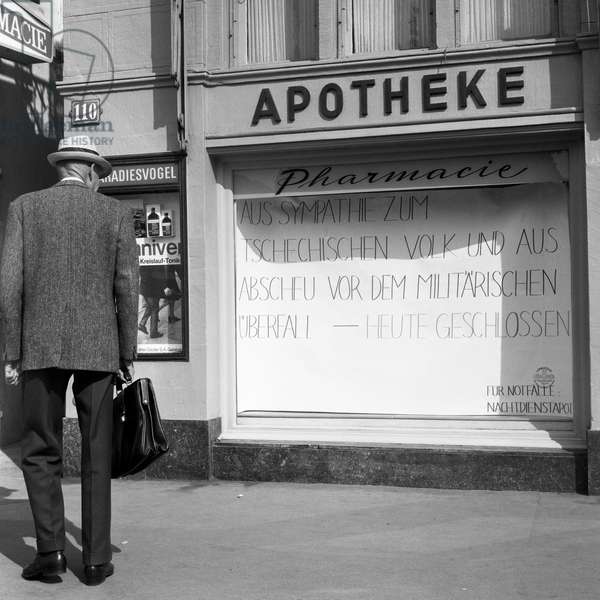

Pharmacy, Zürich, 1968: “Out of sympathy for the Czech people and out of disgust for the military invasion – closed today.”

Refugees without geopolitical value

Refugees from Communist countries were received with open arms. Switzerland, after its appalling behavior during the Second World War, was seeking to anchor itself in western ideology as clearly as it could. Even Tibetan refugees from as far away as China at the outset of the 1960s were found to be “culturally suitable people to live in harmony with (the) Swiss.” Refugees from Czechoslovakia were also welcomed in 1968. There was no quibbling about individual cases. It was just assumed that, as people from a Communist country, they were exposed to “internal pressure from the regime.”

Hans Mumenthaler, the then head of the federal government’s foreigners and social welfare department, justified this policy in 1967 in the following words:

“To demand of an asylum seeker to prove persecution or risk of death is about as realistic as asking him to produce a hair from the beard of the Prophet. Rightly it has been said that such proof could only be provided if the asylum seeker was already in the hands of his persecutors.”

Yet not all victims of dictatorial regimes were viewed the same way; refugees who echoed Switzerland’s position in the Cold War were given preference. This approach was obviously at work in 1973, when the right-wing military junta of General Augusto Pinochet seized power in Chile. The federal cabinet at the time wanted no refugees from the country. This radical view only changed after refugee organizations mounted protests.

Switzerland’s highest court in 2017 ruled that the Swiss People’s Party violated anti-racism laws with this poster, reading “Kosovars cut up the Swiss.” The party said the decision limits freedom of expression.

The fear of the great invasion

On into the 1970s, asylum was a “grace privilege” that the federal government had in its power to bestow. Only in 1979 did Switzerland adopt a legal framework determining who might claim the right to asylum. This was to minimize arbitrary decisions based on geopolitical significance. After 1980, asylum applications increased, independent of the legislation. The global situation had changed. Refugees now came from states, which were supposedly allies in the fight against Communism. In 1980 there was a military coup in Turkey.

Thousands were persecuted, and members of the oppressed Kurdish minority had to flee – some of them to Switzerland. But this time no one was talking about “internal pressure from the regime”. A rejection of an asylum request from a Kurd in the early 1980s reads:

“According to the information he has provided, he was arrested in a military sweep along with many other people from the same village… So this was not a state action specifically directed against the applicant. For this reason, the incident does not qualify him for asylum under our terms.”

Switzerland will not cap the number of Ukrainian refugees

Whereas refugees from Communist countries in previous decades had been assumed to be resisting the regime and therefore qualified for asylum, persecution as a group now no longer counted as grounds for granting asylum. These “new” refugees were regarded with deep-seated mistrust. It may have had some relevance that these people looked different.

Refugees from Sri Lanka, where a civil war broke out in 1983, were considered the first group of dark-skinned people to ask for asylum status. Some politicians found them as “more foreign” than previous refugees. Liberal parliamentarian Hans-Georg Lüchinger in 1984 called for a rejection of entire groups because of their origin:

“It is doubtful whether reception of Tamils in Switzerland should be encouraged through the current application of the asylum process. These fellow human beings from Asia are just not likely to fit in here.”

Furthermore, in view of the increasing numbers of asylum applicants in the early 1980s, there emerged the picture of an endless flow of people which Switzerland needed to protect themselves from. Federal minister Elisabeth Kopp declared in 1985 that Switzerland could not “just open the flood-gates to all those who come for other reasons besides asylum”. The idea that asylum seekers would abuse Switzerland’s hospitality became a major theme in the 1980s, and the initial amendments to the asylum legislation in 1984 and 1988 set the bar for admission higher.

Protestors in Bern in November 2020 advocated allowing more asylum seekers into the country.

Demonizing the asylum seeker

While migration experts speak of a “new kind of” refugee defined as one coming from non-European countries, politicians were quick to divide them up into “true and false refugees.” The idea of the “economic refugee” expressed the fear that people were no longer coming to Western Europe to flee oppression, but poverty and misery – this motivation was even ascribed to people fleeing from civil wars.

At the outset of the 1990s, the right-wing conservative Swiss People’s Party successfully promoted this distinction and popularized a new image of the refugee. In their campaigns, refugees were not just people in need but people who wanted to get residence in the country by any means. Whereas the typical refugee in the Cold-War era was fleeing a brutal Communist regime, by 1989 the asylum seeker was demonized as Communists had been. The stereotype of the refugee was now the drug dealer and knife-wielding criminal.

After the 2001 terrorist attacks in the US, it might have been possible to portray refugees from Afghanistan and Syria as allies in the so-called “international war on terror,” since they were fleeing from the likes of the Taliban and the Islamic State. But the potential wave of solidarity with arrivals from Syria never materialized in Switzerland.

Reprinted from SWI swissinfo.ch. Cet article peut être librement partagé et réimprimé, à condition qu'il renvoie clairement à l'article original.