mer, Juil 20th 2022

As studies continue to tout the benefits of psychedelic-assisted therapy, Swiss patients may have access again to LSD to treat disorders such as depression. The move is actually not so progressive considering that LSD was first synthesized in Switzerland more than 80 years ago, but has been held in bureaucratic purgatory for decades.

Hallucinogenic mushrooms do grow wild in Switzerland, but cultivating them is still illegal.

Last week, the U.S. House of Representatives passed two amendments to the National Defense Authorization Act to expand access to psychedelic treatments for mental health.

This bipartisan reconsideration of the restrictions imposed on psychedelics by the war on drugs illustrates the change of times since Harvard professor Timothy Leary was deemed the most dangerous man in the U.S. for promoting the use of LSD. While fleeing justice, Leary spend time in Switzerland, which has played a major role in the development of psychedelic- assisted therapy.

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and shortly after psilocybin — the hallucinogen component of “magic mushrooms” — were both first synthesized in Switzerland. The compounds showed potential for treating conditions like anxiety, depression, and alcoholism, but political reasons led to a prohibition that stopped research for decades. Now, a renaissance of scientific research on the medical use of psychedelics is happening and Switzerland is, once again, at its center.

Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann was the first person to both synthesize LSD and ingest it.

How did it all start?

The use of psychedelics in their natural form dates back at least 7000 years but western scientists only began to develop an understanding of these substances at the end of the 19th century. Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist, was the first person to trip on acid.

At the time of his discovery, Hofmann had been tasked with researching components of Ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and that Sandoz (now Novartis) was exploiting to treat migraine headaches.

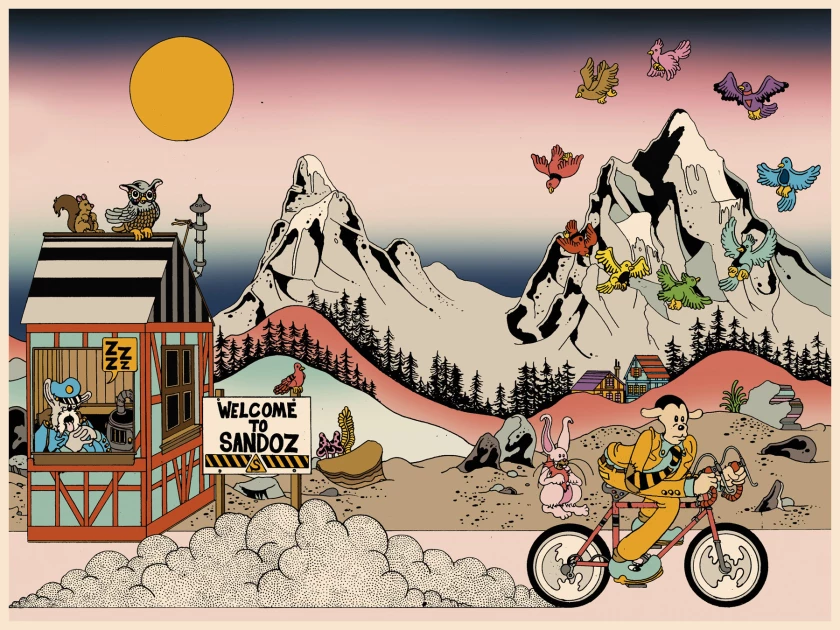

In 1943, he accidentally ingested LSD (short for “lysergic acid diethylamide”), which he had synthesized a few years earlier. Surprised by the strong reaction, he decided to study it further. Hoffman’s resulting, well documented, bicycle ride home while tripping on LSD is still commemorated every April 19th on “Bicycle Day."

Sandoz proceeded to distribute the compound freely to promote research. Early results indicated medical potential and after further testing, LSD was marketed as the drug Delysid in Europe (1947) and the U.S. (1948).

Brian Blomerth’s graphic novel “Bicycle Day” shares the story of Hoffman and his acid-tripping bicycle ride home from work. (Anthology editions)

Another victim of the war on drugs

LSD became a cultural phenomenon. It permeated music (including in Switzerland) and was strongly associated with the 1960s hippie and anti-war movements. As it became more widely used for recreational use, it became more controversial.

The U.S. criminalized it in 1968 and Switzerland followed that same year. Medical research and the therapeutic use of LSD (and other psychedelics) were globally made all but impossible.

During the 1970s and 1980s very few researchers continued to work with psychedelics. Between 1988 and 1993, only five Swiss therapists had a permit for “compassionate use” of LSD and MDMA.

Researcher, Michael Pollan this week debuted a new Netflix series on psychedelics.

The renaissance of medical research on LSD

A new generation of behavioral researchers picked up psychedelics again in the 1990s. The first legal study of psychedelics (specifically, DMT) was conducted in 1991 in the U.S. Other studies on MDMA and psilocybin followed in the U.K., Germany, and Suisse. But not all psychotropics advanced equally.

“It was practically impossible to do research on LSD in the 80-90s and therefore most researchers started with MDMA or psilocybin. LSD was clearly more stigmatized and everybody had associations while the other substances were less well known,” said University of Basel’s Dr. Matthias Liechti.

Dr. Katrin Preller, Laboratory Head at the University of Zurich, adds that the longer sessions needed for LSD studies — more than 10 hours of use, compared to six hours for psilocybin, for example — contributed to it falling behind other psychedelics in terms of clinical trials.

It was not until 2008 that legal research on LSD became a reality again; starting at the foot of the Swiss Jura mountains in Solothurn. The 2006 Symposium celebrating Hofmann’s 100th birthday created momentum and Peter Gasser, a therapist acquainted with LSD during the 1988-1993 window, was granted approval to carry out the first controlled study of LSD-assisted psychotherapy in more than 40 years.

Hofmann received the news of the study’s approval just before his death in 2008. After the study, the compassionate use of psychedelics was reinstated and Dr. Gasser’s patients were among the first beneficiaries.

In 2012, Dr. Matthias Liechti’s group initiated their first LSD trial at the University of Basel and has been producing promising results ever since. London, Zurich, and Chicago followed soon with their own trials that add up to at least 16 as of July 2022 — nine of them completed.

In psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, a trained therapist guides the patient in dosing and through their experience. It is common for the patient to wear a blindfold and noise-cancelling headphones. (Microdose Psychedelic Insights)

A brave new world of treatment

Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy could be used to treat debilitating mental-health disorders such as PTSD, alcoholism, major depression and other disorders that kills millions of people worldwide every year, according to the results of the latest studies. Moreover, these psychiatric disorders cost billions worldwide in lost productivity.

More than 70% of patients who took psilocybin found a 50% reduction in their symptoms in less than one month – and the benefits have lasted, according to a study published in 2020.

“People get locked into disorders like depression because they develop this system of thinking which is efficient, but wrong,” psychopharmacologist David Nutt told science journal Nature. Psychedelic therapy appears to break the brain’s cycle of rumination; essentially, opening the brain up to new ideas about the past and future.

“There is a growing evidence base to the principle that this is very much about a synergy between drug-induced hyper-plasticity and therapeutic support,” says Robin Carhart-Harris, an Imperial College London neuroscientist.

For now, getting access to psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy means taking the drug in a therapy setting under close watch of a trained psychotherapist; and, one session may be several hours, if not the whole day. Most drugs which treat anxiety and depression can be picked up at a neighborhood pharmacy. That said, for many psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy may be effective more quickly with fewer side effects than the most popular drugs on the market.

Last month, the U.S. company Ceruvia announced that it would provide free, pharmaceutical-grade LSD to researchers, just like Sandoz did 70 years ago. The next challenge will be shipping it across borders.

The Swiss are more in favor of pursuing something — even something controversial — “when something is framed in a scientific context,” says Swiss publisher Roger Liggenstorfer.

Why Switzerland?

Financially, the land of pharma is no unlikely place for the invention and development of LSD, but the mathematics of it are complicated: the patent has expired and finding a way to protect and profit off intellectual property will be a challenge for investors. Thus, while the business case becomes clear, the Swiss government have had to pick up a significant part of the bill.

There also seem to be cultural reasons for Switzerland’s leading role in developing LSD. Hofmann’s long-time friend and publisher Roger Liggenstorfer says “the Swiss are pragmatic people. When something is framed in a scientific context, and for a limited time, then they are in favor of studying it”.

Liggenstorfer has contributed to this evidence-based approach himself by introducing drug checking in Switzerland and through Nachtschattenverlag, his publishing house aimed at educating on drug consumption.

A banker by training, Liggenstorfer changed careers in 1980 after being sentenced for “incitement to drug consumption” because he was selling books about marijuana. Now, the Swiss Federal Office for Culture sponsors his work — a sign, he says, that times have changed.

And they have: Switzerland’s drug policy took a dramatic shift away from prohibition. Today, it has drug consumption rooms and is about to launch a first cannabis sale pilot.

“We are a country doing a lot of research and there has been a tradition in investigating substance-assisted therapy that almost never fully stopped… we may be more used to the process, both as investigators and regulators,” wrote Dr. Liechti.

“I’m in a country who is host to the invention of LSD…[but] we have renounced for 30 years to develop answers to people suffering from pain,” said former president of Switzerland Ruth Dreifuss during a discussion on drug policy and human rights in Geneva last month. It would appear Switzerland is looking to recover those lost years in the days to come.

Cet article peut être partagé et republié sur d'autres sites web sans notre autorisation, à condition qu'il renvoie à la page originale d'UltraSwiss.