Jue, Mar 3rd 2022

Tens of thousands of Swiss residents gathered in the streets of Zurich, Lausanne, Bern, and Geneva this week, draped in Ukrainian flags, and holding signs reading “Stop Putin” and “No War.” As Swiss leadership remained quiet earlier in the week, the chant of their citizens – punctuated by cowbells and alphorns—became louder and louder until Switzerland replied to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Protesters disrupt normal traffic outside of the United Nations headquarters in Geneva.

“The Swiss Federal Council has decided today to fully adopt European Union sanctions,” Swiss Confederation President Ignazio Cassis said during a press conference. In adopting sanctions, Switzerland has frozen assets belonging to Russian President Vladimir Putin, Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin and Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, as well as 367 individuals sanctioned last week by the EU. Moreover, the country closed its airspace to Russia and impose entry bans against individuals who are connected to the Russian president.

“It is an unparalleled action of Switzerland, who has always stayed neutral before,” Cassis added. (Read more: Switzerland’s complicated history of neutrality)

Swiss Confederation President Ignazio Cassis held a press conference earlier this week to announce that Switzerland would move away from neutrality to support Ukraine.

Money talks

Not only was the move a historical one for the small, Alpine nation, it is one which will badly cripple Putin and his friends as Switzerland is by far the largest recipient of Russian private capital. The country has long been a popular hub for storing wealth among Russian oligarchs, as Swiss neutrality has long ensured that the Swiss franc is a stable currency to invest in.

Anywhere from $5 billion to $10 billion of private Russian money flows into Switzerland every year, according to the Bank of International Settlements. Russian nationals currently house roughly $11 billion in Switzerland, or about one-third of the money sitting in Swiss banks. After including assets held through offshore accounts, brokerages, and other investments (such as homes and yachts), that number soars to between $100 and $300 billion in 2022, according to Swiss Info.

Moreover, about 80% of Russia’s commodity trading goes through Switzerland, most of it through trading firms with stakes in Rosneft, a major Russian oil company.

Picturesque Gstaad is one of the most popular places for Russian billionaires to own property.

“To play into the hands of an aggressor is not neutral. Having signed the Geneva convention of human rights, we are bound to humanitarian order,” Cassis said, adding “Other democracies shall be able to rely on Switzerland; those standing for international law shall be able to rely on Switzerland; states that uphold human rights shall be able to rely on Switzerland.”

But untangling Russo-Swiss relations is no small feat – one that will hurt both countries financially – as their complicated relationship began centuries ago.

A history lesson

The first mention of a Russian/Swiss friendship appears in the late 1600s when Czar Peter I made Swiss soldier François Lefort one of his top advisers to the young ruler’s modernization campaign for his country. The friendship opened the door to many other Swiss educators, artists and scholars who were attracted to the Russian Empire. Swiss architect Domenico Trezzini was the general manager of the construction of Saint Petersburg until 1712 and is the father of Petrine Baroque, best exemplified in the Peter and Paul Cathedral, as well as Russia’s first museum, the Kunstkamera.

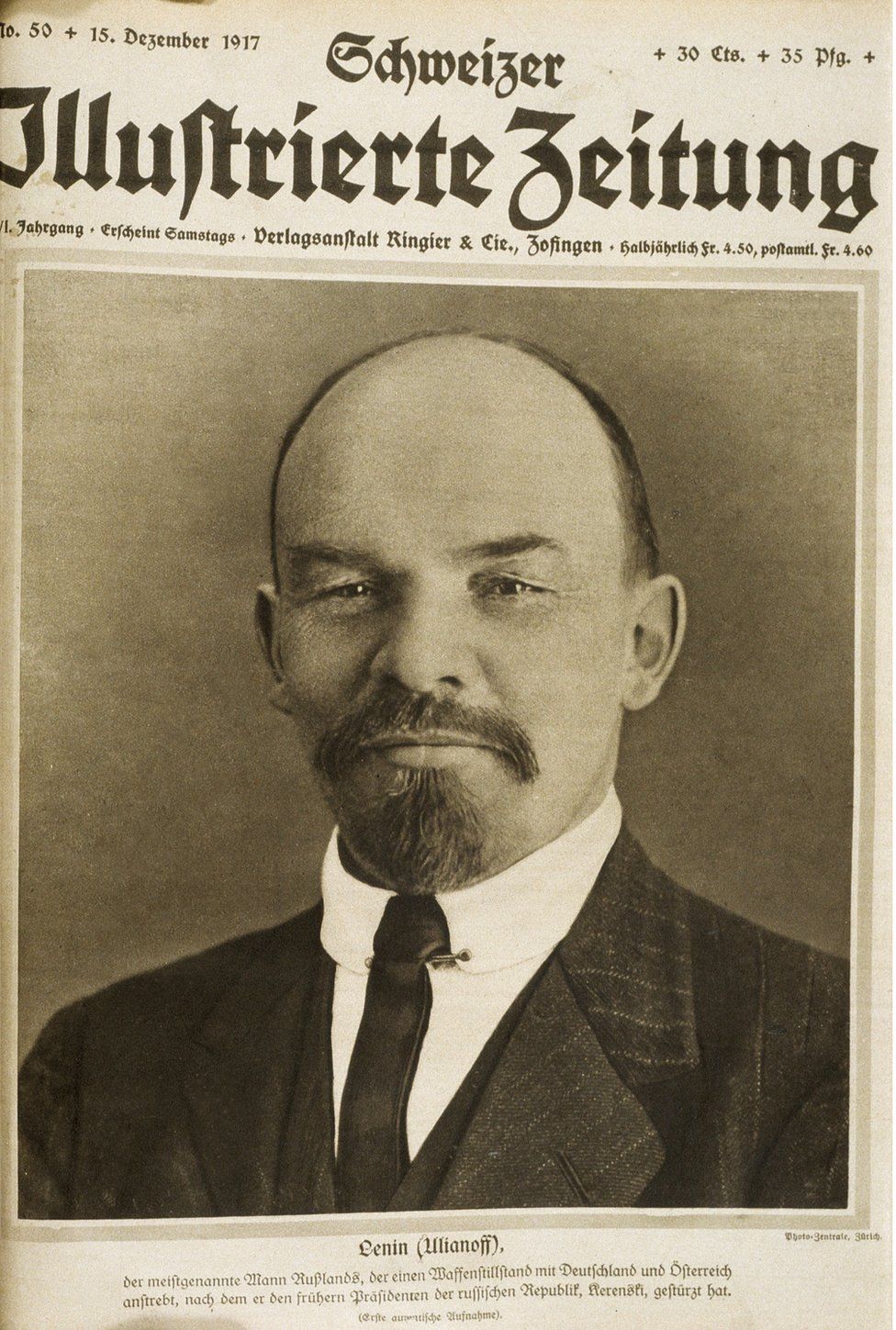

Russians first found their way to Switzerland in large numbers around 1799 during the early Napoleonic Wars fought on the Swiss-Italian border. In retaliation to the devastation caused there, 8,000 Swiss men joined Napoleon’s army that invaded Russia in 1812 – and only a few hundred survived. Still, Switzerland sought good relations with Russia by opening a consulate in Saint Petersburg in 1816. Throughout the 1800s many anti-czar Russians moved to Switzerland, at a time when the country was gaining a global reputation for freedom and neutrality. Some of the more famous Russian exiles include Alexander Herzen (the “father of Russian socialism”), who became a Swiss citizen in 1851 and Vladimir Lenin, who returned to Russia to lead the 1917 uprising.

The front page of a Swiss newspaper announces Lenin’s departure.

When Russia’s revolution was at its apex in 1923, Switzerland broke off diplomatic relations and did not resume them until after World War 2. When the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991, the number of Russian travelers to Switzerland surged, bringing with them wealth and assets. Relations between Switzerland and Russia appeared to improve, even culminating in hosting President Putin and U.S. President Joe Biden last June for peace talks.

Switzerland and Russian espionage

A 2018 Swiss intelligence report revealed that one in four Russian diplomats based in Switzerland is a spy. In the months following the report, two such agents were arrested for trespassing on a Swiss laboratory and a compatriot of President Putin’s was arrested in Geneva with false license plates, numerous cell phones, cameras, and laptops. That man was sent to spy on dissidents living in Switzerland who had fallen out of favor with the Kremlin, according to German language newspaper SonntagsZeitung.

In both cases, the spies avoided public trial and were sent back to Russia, likely in order to sidestep a diplomatically sensitive matter with a country that holds so much wealth in Swiss banks.

A 2018 Swiss Intelligence report found that one in four Russian diplomats living in Switzerland — mostly in Geneva (above) — are spies for the Kremlin.

Russia’s interest in Switzerland

About 17,000 Russians currently live in Switzerland (for reference, about 19,000 Americans live in Switzerland), and they are the most likely expats to pursue Swiss citizenship according to a 2020 report.

“For people who live in less democratic regimes, the possibility of participating in elections and voting is particularly attractive,” said Professor Philippe Wannerat, author of the report. He added that a Swiss passport makes mobility easier than a Russian one.

In fact, Putin’s supposed girlfriend, former Olympic gymnast Alina Kabaeva, gave birth to their daughter in 2015 in Ticino, Switzerland. Swiss newspapers reported the event, but outlets that did so in Russia were quickly muffled.

Several uber-wealthy Russian oligarchs continue to reside in, or at least, own homes in Switzerland, including:

Según The Bell, many Russian oligarchs flew to Switzerland privately at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, intending to use the Swiss healthcare system if necessary.

A still burning building in Kyiv signifies where Russian-Ukrainian relations lie today.

¿Adónde vamos ahora?

The Swiss response to invasion of Ukraine has been outspoken and focused on humanitarian aid. There are large-scale efforts and grass-roots aid efforts springing up in every part of the country. A few expat bloggers have helped organize trucks going from Zurich and Geneva to Moldova and Poland, filled with clothing, blankets, medicines and food. One such blogger, Polish expat Olga Sokolik, said the response has been overwhelmingly good, but she has still received negative messages from those who support Russia’s war. She remains undeterred.

Refugees wait in line at the border of Ukraine and Poland earlier this week.

Would you like to support Ukrainian refugees? Here are UltraSwiss’ tips:

-Consider making donations to humanitarian groups that are local to Ukraine, such as:

-Follow @knowabroad and @parentvillegva on Instagram for the latest donation needs on trucks leaving Geneva and Zurich. (For example, they have been inundated with clothing, but now need diapers, phone chargers and warm shoes for children.)

-Book Airbnbs in cities such as Kyiv and Kharkiv – not for a vacation, but as a means to make a direct donation to residents most affected by warfare.

-Purchase Ukrainian made goods via Etsy – again, with no intention of receiving the goods, but to make direct donations to affected Ukrainians.