Mar, Feb 28th 2023

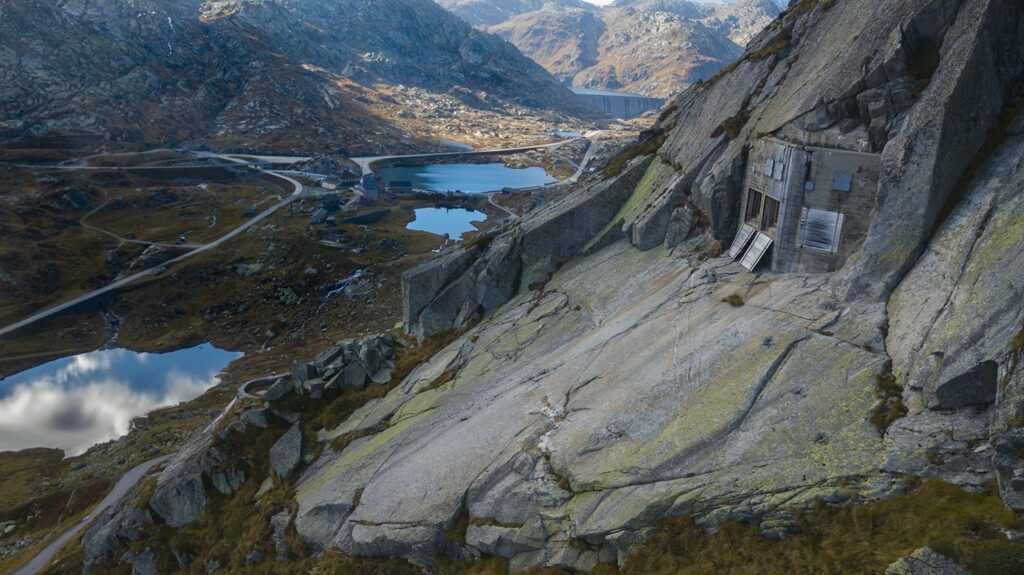

The tunnels remain under Switzerland, even if the threat of invasion has waned (Credit: Jeff Skrob).

While its neighbors fought bloody battles all around Switzerland during the 20th century, the neutral nation reinforced its borders with a series of fortresses, bunkers and entry points rigged to blow at at the first sign of invasion – effectively walling off the small country to the world, need be. The elaborate defense plan is called the Swiss National Redoubt.

An iconic image of Swiss military patrolling the Alps during World War II.

The Swiss National Redoubt

The Swiss government first developed the strategic insurance policy to respond to foreign invasion in the 1800s using Switzerland mountainous topography as a defense. This strategy was integral to Switzerland’s abiding policy of armed neutrality, dating back to the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

In the 20th century, the landlocked country supported both the Axis (Germany, Italy, and Japan) and Allied (U.K., U.S., U.S.S.R.) countries in World War II. With Switzerland situated between Italy and Germany, fears of an invasion were heightened as Germany considered using the alpine country as a passageway or even annexing it as part of the Third Reich.

After the Axis powers defeated France in 1940, Switzerland lost a significant ally. Swiss General Guisan realized then that defending his country’s borders was futile against a much stronger German army, so he moved his troops away from the front lines, relinquishing the lowland border cities to enemy forces. Guisan retreated the Swiss army into a network of impassable mountain fortresses across the Alps. (Read more: Tracing Nazi gold through Switzerland).

Switzerland ramped up its National Redoubt by building more than 8,000 fortified and hidden bunkers and warehouses – a chain of citadels – into the country’s mountainous terrain, providing a natural defense against invasion. Given its geographical vulnerabilities, the country’s full scale of reinforced clandestine positions and barricades was a closely guarded secret. Still, some fortifications were kept in plain sight as part of a broad effort of interception and deterrence.

Army barracks frozen in time in the Sasso da Pigna fortress near the border of Italy (Credit: Sasso San Gottardo).

The Swiss government implemented a three-step plan during World War II as a precautionary move to defend itself from overzealous invaders.

The first step included wiring hidden artillery on all bridges connecting Switzerland to its foreign neighbors. Even the historic Säckinger Bridge, connecting Switzerland to Germany, was rigged with explosives. Moreover, concealed bombs on hundreds of key Swiss highways, tunnels, and railroads were designed to quickly destroy the infrastructure, while explosives along exterior mountain slopes would trigger artificial rockslides.

Switzerland’s natural environments were extensively weaponized – all wired for self-destruction of its infrastructure – to hinder an invading army. More than 3,000 points of explosions are publicly known to have been installed throughout the tiny Alpine country.

The second step involved migrating the population deep into 300,000 hidden and impenetrable bomb shelters. These underground bunkers, situated below bucolic villages and built to withstand an attack, had adequate resources to accommodate the entire population for extended periods. Each stronghold was a quarter mile deep and two stories high. They were equipped with kitchens, toilets, bakeries, hospitals, dormitories, and separate sleeping quarters for officers.

To accommodate the Swiss military, camouflaged entryways large enough for military tanks to pass through were carved directly into the rockface and covered with foliage to blend with the surrounding terrain. Each military fortress, designed to hold 120 people for one month, had a war room, radio room, water tank, generator, and even a disinfection room in case of a chemical attack. In addition, some fortresses housed artillery and hidden hydroelectric dams in the event of mass bombings, and some served as hangars for fighter planes.

The third step included constructing reinforced defensive positions on strategic outposts resembling ordinary homes. The purpose of these Cold war-era bunkers made to look like farmhouses was to deter aerial attacks as well as ambush and deter advancing armies.

Fortunately for Switzerland, these plans never saw the light of day as Hitler’s army never advanced into Switzerland.

The Sasso San Gottardo fortress is open as a museum (Credit: Sasso San Gottardo).

The National Redoubt’s clandestine fortresses were shrouded in secrecy from World War II through the end of the Cold War. Many medium-sized fortifications and more than 10,000 smaller command posts and bunkers remained shut down for decades. And visiting the large command fortresses that anchored the chain of citadels across the Alps was forbidden by the military.

But by the 1990s, western Europe had already seen a relative period of peace and political stability for a few decades. To that end, the Swiss government had begun the process of disarming and removing the explosives hidden inside the country’s railways, bridges, and tunnels. The vast network of secret bunkers was declassified by the turn of the century, mainly because soaring maintenance costs to keep them operational were prohibitive to the national budget. Moreover, abandoning these fortresses was not an option because of the high costs associated with decommissioning them.

In one instance, this led to private companies using these secure fortresses as server farms and data repositories as they are fully protected from external electromagnetic impulses that can occur from nuclear explosions. In another, researchers utilized the bunkers as storage facilities with instructions on decoding and reading all known data storage formats – even antiquated ones such as floppy discs – so that if knowledge is unforeseeably lost, future generations can still access and decipher our data storage devices correctly.

However, because of military downsizing, the fate of the remaining fortresses is uncertain. As a result, there have been demands to demilitarize all of them, despite the estimated multi-billion-dollar cost.

Many bunkers still remain, hidden in plain sight (Credit: Sasso San Gottardo).

As the secret fortresses become declassified, they are getting a fresh start as the shadow of war has faded with time.

The top-secret fortress, Sasso da Pigna – built in 1941 and located at the Gotthard Pass – was converted into a museum after someone tried to break into it, forcing the government to declassify it. Now, visitors are transported to the heart of the underground military complex – frozen in time – complete with gun batteries, bunker cannons, the command center, army barracks, and an artillery room.

An artillery bunker not far from the Sasso da Pigna fortress was transformed into a cavernous, 17-room hotel, La Claustra, in 2004 by Swiss architect Jean Odermatt.

Another artillery fortress located 650 feet below the Giswil mountain, once used for storing ammunition and spare parts for guided missiles, was bought by the Swiss cheese maker, Seiler Kaserei AG. The cheese company now makes wheels of raclette cheese in the former bunker’s tunnels, where the temperature and humidity levels are ideal for the cheese’s aging process.

Although many hidden fortresses have found a new lease on life, thousands still remain hidden beneath Switzerland’s idyllic pastures and fairytale chalets.

Este artículo puede compartirse y volver a publicarse en otros sitios web sin nuestro permiso, siempre que se enlace a la página original.